International Symposium: Haunted Nature

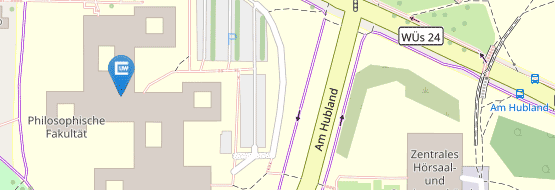

University of Würzburg

November 8-9, 2019

Organizers: Sandy Alexandre (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) and Sladja Blažan (Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg)

Speakers

Sandy Alexandre (Massachusetts Institute of Technology)

Sladja Blažan (Universität Würzburg)

Justin D. Edwards (University of Stirling)

Catrin Gersdorf (Universität Würzburg)

Alexandra Hauke (Universität Passau)

Johan Höglund (Linnaeus University)

Dawn Keetley (Lehigh University)

Elizabeth Parker (University of Birmingham)

Elisabeth Scherer (Universität Düsseldorf)

Agnieszka Soltysik Monnet (University of Lausanne)

Elmar Schenkel (Universität Leipzig)

In “On naïve and sentimental poetry” the German poet and philosopher Friedrich Schiller proposes the idea that the pleasure humans take in nature is not aesthetic but moral. Nature, in this text, is described as a sovereign entity that functions according to its own logic completely divorced from the human. Humans can recognize this harmony and unity in nature (Schiller uses the examples of plants and sounds in the forest) and see in it something that they have lost. This recognition produces a sublime emotion, a mixture of pain and longing. “Sie sind, was wir waren, sie sind, was wir wieder werden sollen [They are what we were, they are what we should become again].” With this text published in 1795, Schiller sets a whole generation of writers, who came to be known as Romantic writers, in relation to nature through alienation and separation. Representations of nature since the Romantic period until the late twentieth century perpetuate this distance between nature and men in particular. Currently, various contemporary scholars dispute this long-standing separation between nature and culture. Bruno Latour, most famously, claims that the idea that with the rise of science and the beginning of modernity, we moderns have completely separated from our primitive, premodern ancestors, is simply a faith, a belief we cherish. According to Latour the separation between nature and culture never happened. Instead, nature has all along been an active participant within our lives. Various scholars have followed his lead in arguing against the view of nature as external to culture. Stacy Alaimo’s focus on the human body leads her to argue that human corporeality is in fact a transcorporeality – a corporeality always also inscribed in its natural environment. According to Alaimo, “The human is always intermeshed with the more-than-human world.” The active role of the natural environment in our assumed human-centric lifestyles, however, has led Simon Estok to coin the neologism “ecophobia” in order to describe nature as a source of anxiety for humans. But what exactly is it about nature and the natural world that humans have to fear?

In this symposium, we will discuss ideas relating to the agency of nature, particularly the forest, the swamp, and the woods, through the concept of haunting. Haunting is one of the very few literary concepts capable of expressing the uniquely nonhuman vitality of nature. In fact, seen from a nonhuman, or new materialist standpoint, haunting has always recognized the vitality of nature and its capacity to act as an agent, or to use a more radical term introduced by Bruno Latour, as an “actant.” In our symposium, we would like to define just how this actant incorporates, performs, and releases its hauntings.

Throughout the symposium, some of the questions we will explore include but are not limited to the following:

- How has nature been entangled with ideologies of race, gender, and citizenship? For example, how do we account for the fact that most forests in nineteenth century North American narratives seem to be predominantly haunted by native American spirits? How do representations of wilderness in North American literature relate to haunting?

- In one of the first articles on the so-called “ecogothic,” Simon Estok writes about “ecophobia” as a term that describes “contempt and fear we feel for the agency of the natural environment.” What are some current representations of ecophobia and what is their effect?

- How does historic knowledge inform our various and sundry experiences of the natural world?

- How can we theorize hauntings as reparations claims--that is, as a way for Native Americans and black Americans to re-appropriate or even recuperate what was stolen from them?

- What do we culturally inscribe into nature when we call it haunted? Who is the agent? Who is haunting? And who is haunted?

- What exactly do literary ghosts have to say about deforestation, climate change, and other human-triggered natural disasters that ultimately impact the very places they want, choose, or need to haunt? In other words, how might ghosts and their respective hauntings be seen as forms of environmentalism?